Insomnia should be considered a distinct disorder rather than a secondary symptom of another medical or psychiatric illness, says the author of a new consensus guideline on managing insomnia in primary care (recently published in The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders).

“Insomnia is a highly prevalent problem that’s often under-treated and oftentimes under-recognized,” said Russell Rosenberg, MD, the chief science officer of NeuroTrials Research, Atlanta School of Sleep Medicine.

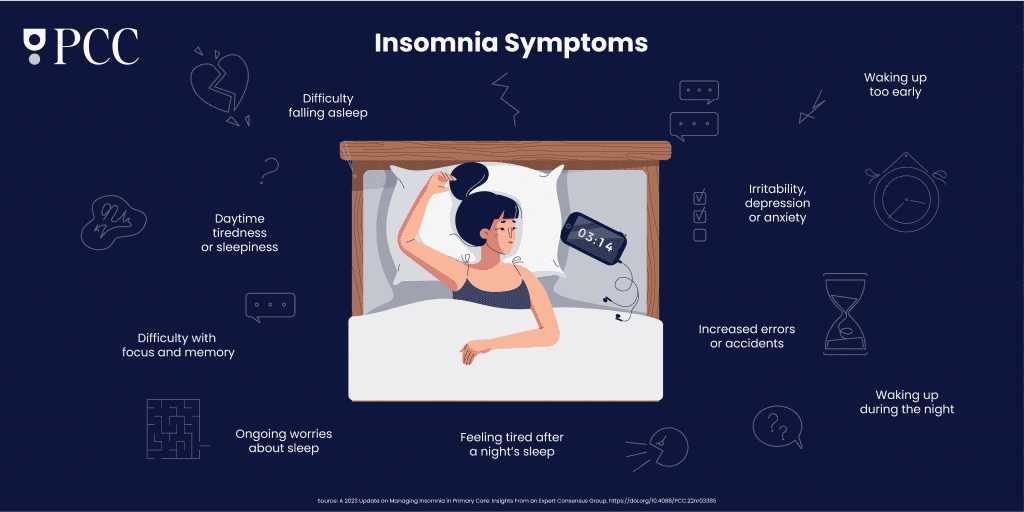

Any time a patient has difficulty falling or staying asleep, insufficient sleep duration, early waking, or next-day impairment on a regular basis, it’s time to consider a targeted, individualized approach to therapy. The Insomnia Working Group, led by Rosenberg, met in March 2022 to review data on available therapies and share evidence-based practices for helping people get a better night’s sleep.

A 2023 Update on Managing Insomnia in Primary Care

Prescription Sleep Meds May Up Risk of Dementia by 79% in White Seniors

Bad Dreams and Nightmares Preceding Suicidal Behaviors

Here are their findings.

Comorbidities

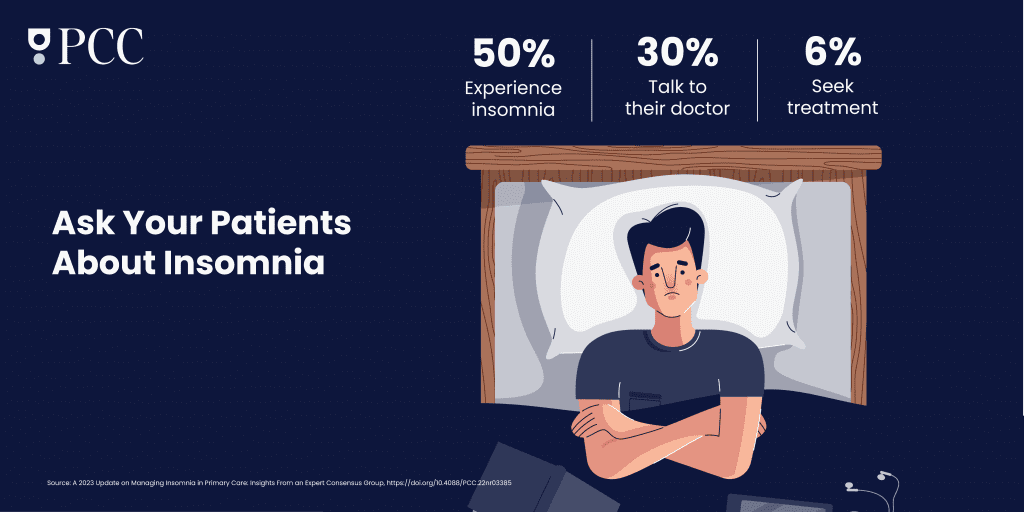

Almost 50 percent of primary care patients experience insomnia, but only 30 percent of them mention the issue to their physician, and only six percent seek medical help for difficulties sleeping. By Rosenberg’s estimate, somewhere around 17 percent of patients have insomnia that rises to the clinical level of insomnia disorder.

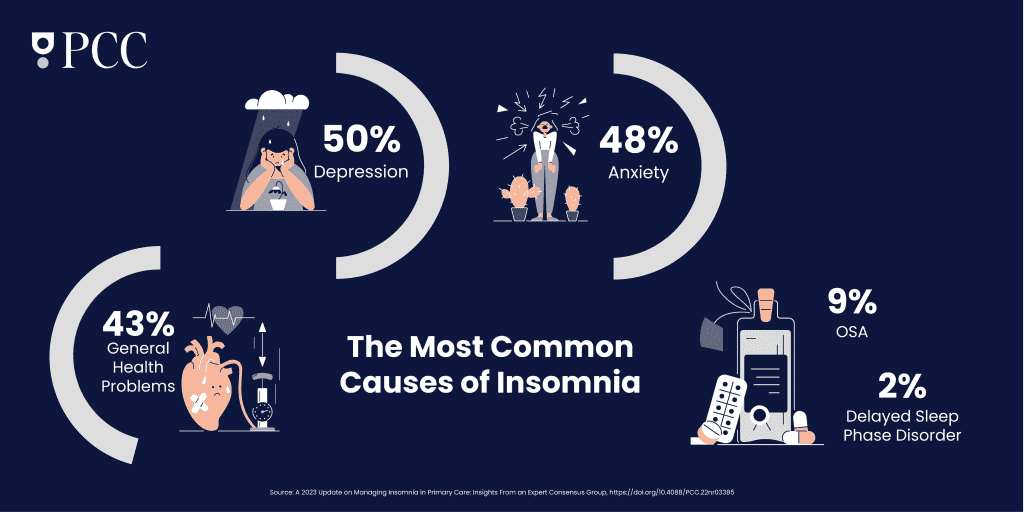

Clinicians shouldn’t make light of sleep troubles, Rosenberg said. Managing slumber habits can be hugely beneficial in dealing with physical and psychological outcomes across the board. But the relationship between insomnia and other medical conditions is complex and “can go both ways as sort of a chicken-and-egg thing,” Rosenberg explained. It’s common for patients who toss and turn on a regular basis to be diagnosed with comorbidities like depression, cardiovascular disease, or in more recent history, COVID-19.

“We don’t exactly know the relationship between a viral infection like COVID, and sleep and insomnia,” Rosenberg admitted. “But it could partly be due to the anxiety around contracting the disease.”

Nonpharmacologic Therapies

The new guidelines recommend trying a combination of lifestyle changes, improved sleep habits, and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) before trying a sleeping aid or in combination with the aid.

CBT is the first line of treatment recommended by major sleep organizations, Rosenberg said. It’s a behavior change technique that involves non-drug approaches such as sleep hygiene, relaxation, and cognitive strategies to improve sleep. For example, changing negative thought patterns related to depression and anxiety can increase a patient’s chances of getting to sleep and staying asleep.

Medication can be used along with CBT, Rosenberg explained. However, patients often reach for over-the-counter remedies instead, sometimes without mentioning it to their doctor.

“Clinicians should educate patients about the risks and benefits of over-the-counter options, including herbal remedies and supplements,” Rosenberg said. “It’s important to stay informed about the use of nonprescription drugs to make sure they aren’t actually making things worse.”

For example, Rosenberg said many patients are turning to marijuana in hopes of better shuteye, especially as it is legalized and decriminalized in many states. But this can backfire because marijuana use is sometimes a contributor to chronic insomnia.

Pharmacological Management

While he’s not an advocate for using medication as a first line treatment for insomnia, Rosenberg said he sometimes recommends it as an effective short term strategy.

Various neurotransmitters act as a kind of messenger service between neurons in the brain during the sleep-wake cycle. The balance between these neurotransmitters constantly shifts throughout the night, which is something clinicians can use to their advantage when prescribing sleep drugs, Rosenberg pointed out.

The insomnia drugs generally fall into three different categories:

- Over-the-counter sleep aids (discussed above)

- FDA-approved prescription sleep drugs

- FDA-approved prescription drugs used off label.

Doctors need to use careful judgment and consider the patient’s preferences, previous responses, and potential side effects when deciding on a pharmacological treatment, Rosenberg cautioned.

The most commonly prescribed medication for insomnia in the US is off-label trazodone, but there is limited evidence of its safety and effectiveness, Rosenberg noted. Other off-label drugs that are sometimes used for insomnia include anticonvulsants and atypical antipsychotics and increasingly, antidepressants that target serotonin and other receptors involved in sleep and wakefulness. Benzodiazepines and related drugs are also commonly prescribed but these can have significant side effects such as impaired thinking and memory, risk of dependence, and rebound insomnia when the patient stops using them.

The newest sleep aids like suvorexant are known as dual orexin receptor antagonists, or DORAs. They work by blocking the specific receptors involved in arousal and wakefulness. In studies, the most recently FDA approved DORA, lemborexant, stacked up well against other insomnia drugs for safety and effectiveness.

“Most people who utilize these drugs use them for short periods to try to get back on track, but of course there are people that use them long term and they should consider any long term adverse effects. It’s important to weigh the benefits of taking a sleep drug as well as be aware of some of the negative effects we sometimes see. Not everybody can tolerate these drugs,” Rosenberg said.

Read the complete description and consensus guideline recommendations for insomnia here.