Even hair follicles want to ‘stay in touch’ with their roots. Research just published in Science Advances suggests that the structures that anchor individual strands of hair in place are capable of a sensory experience that was previously unknown to science.

Beyond making sure that hair stays put, hair follicles also help regulate temperature and manage sweat. While humans don’t use whiskers to feel around the same way animals like cats and dogs do, our sense of touch is advanced enough to assist us in navigating the world and even process emotions.

SLYM Membrane Was Brain’s Best Kept Secret Until Now

Two Sisters May Change Our Understanding of Parkinson’s Disease

The Mane Results

It works like this: special nerve cells in the skin send touch information to the brain. So do other skin cells. In the new study, Imperial College London explored the interaction between these nerve cells and human hair follicles to see what and how they experienced touch.

The researchers started by collecting scalp skin samples from men aged 23 to 54 who were undergoing hair transplant surgeries and also gathering up leftover skin from abdominoplasties to establish keratinocyte cultures. A keratinocyte is a skin cell that produces keratin, the protein that makes up the outer layer of skin, hair, and nails.

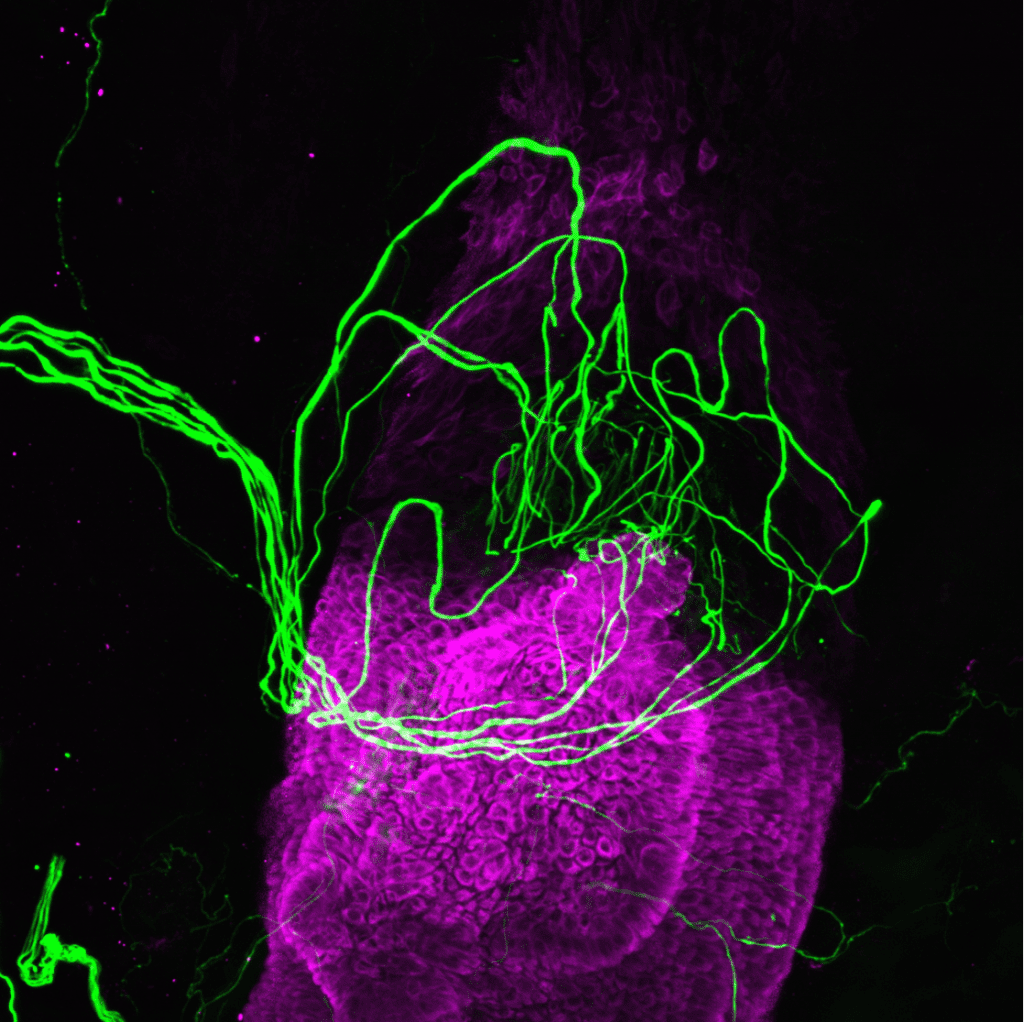

The researchers then processed the samples using various techniques. They used whole-mount immunolabeling to highlight specific tissue parts for microscopic viewing. Volumetric imaging captured detailed 3D tissue pictures. They also analyzed RNA extractions for gene expression. Additionally, they cultured different cell types and subjected them to a variety of treatments to observe the responses.

This complex set of experimental methods helped demonstrate how the nerve cells sent signals to the brain that process touch sensitivity. Cells known as outer root sheath, or ORS, cells in the hair follicles interacted with these nerve cells. When something pressed against or moved the ORS cells, they released chemicals like serotonin and histamines to help modulate the response of the nerve cells.

“This is a surprising finding as we don’t yet know why hair follicle cells have this role in processing light touch,” said lead author Claire Higgins, a professor at the Imperial College London’s department of bioengineering. “Since the follicle contains many sensory nerve endings, we now want to determine if the hair follicle is activating specific types of sensory nerves for an unknown but unique mechanism.”

Even More In Touch

Further testing showed just how sensitive the ORS cells were. The number of times something touched the hair follicle influenced the amount of serotonin and histamine released. More frequent brushups led to a greater chemical release.

Compared to how skin cells react to contact, the researchers noted that while both types of cells respond to touch by releasing histamine, only the ORS cells released serotonin. This implies that hair follicles have a unique way of sensing and responding to touch compared to the rest of the skin. Interestingly, the researchers observed that ORS cells also had the ability to revert into regular skin cells when needed, like during wound healing, but still maintained their unique touch-sensing abilities.

Previous research on ORS cells found that they emit ATP (Adenosine Triphosphate), a molecule that serves as a signaling agent to communicate with nerve cells. The new findings add complexity to this model by showing that the communication between ORS cells and nerve cells isn’t just a one-way street with ATP as the only traffic light. There might be other molecules or mechanisms involved, making the process more intricate than originally observed.

Skin Deep Science

These insights into the touchy feely powers of hair follicles could potentially lead to new treatments for conditions related to touch sensitivity or insensitivity. They might have implications for treating other types of skin problems as well.

“This is interesting as histamine in the skin contributes to inflammatory skin conditions such as eczema, and it has always been presumed that immune cells release all the histamine. Our work uncovers a new role for skin cells in the release of histamine, with potential applications for eczema research,” Higgins said.

The researchers say they need to conduct further experiments on living organisms to validate the study’s results. Since some nerve receptors exist only in hairy skin, the team will explore specialized signaling mechanisms within the hair follicle for these nerves.