Two sisters with different genetic mutations showed varying severity of Parkinson’s Disease (PD).

In a new study published in the journal Neuron, one sister developed a milder form of PD at age 49 due to a mutation in the PINK1 gene. The other sister, who had the same PINK1 mutation plus an additional parkin mutation, experienced a more severe form of PD, diagnosed when she was just 16 years old.

“We were surprised at this and it took us several years of detailed work in the lab to uncover the mechanism behind the difference,” said Dimitri Krainc, MD, the chair of neurology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, and the director of the Simpson Querrey Center for Neurogenetics.

Cholinesterase Inhibitors for Delusions and Hallucinations in Parkinson’s Disease

Brain-Targeting Drug Similar to Ozempic Shows Promise in Parkinson’s

500% Rise in Parkinson’s Linked to a Common Dry Cleaning Chemical

Genetic Testing for Parkinson’s

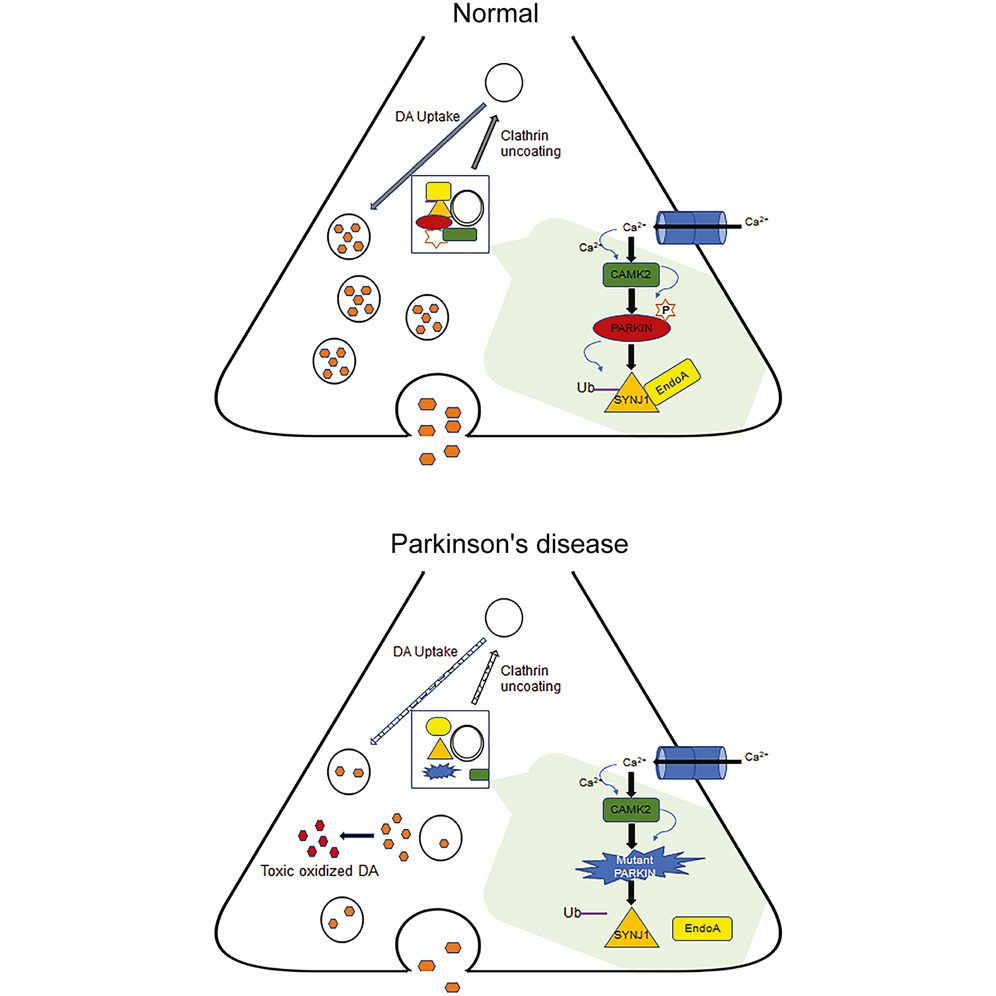

Krainc’s team used advanced lab methods like immunocytochemistry and confocal microscopy to study how neurons function. They focused on aspects like synaptic transmission, which involves the transfer of signals between neurons, and neuronal firing patterns, which are the patterns of electrical activity in the brain. When mutations were found in the parkin and PINK1 genes, these functions changed.

The team also studied key proteins, SYNJ1 and endophilin A1, using specialized techniques. These included co-immunoprecipitation and Western blotting, which track protein interactions, as well as calcium imaging and optogenetic stimulation for real-time monitoring of how neurons behave. Results showed that mutations in the parkin gene significantly disrupted how neurons function, affecting these crucial proteins.

Understanding Mitochondrial Function

PINK1 and parkin genes have long been implicated in PD. They help clean up old and worn-out parts of the cell called mitochondria, a process known as mitophagy. When these genes don’t work properly due to mutations, the old mitochondria aren’t repaired. This can cause problems in the cells, issues that may eventually lead to PD.

Krainc said the study was able to apply the information collected from the sisters to other patients. “We think the wider implications are how neurons communicate via their synapses and the early pace of neuronal dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease that precedes degeneration,” he explained.

A Shift in Perspective

The study provides insights into how genetic mutations influence the severity and progression of PD. According to Krainc, the work might also offer one explanation for why clinical trials looking at Parkinson’s therapies often yield poor results.

“In a clinical study, a small group of patients may respond positively, but because they are grouped with other patients who may have a different biological basis for the disease, the study is considered a failure,” he said.

Krainc emphasized the importance of classifying patients not just by their clinical diagnosis but by the specific features of their disease. This includes the genes involved and specific changes to the brain at the cellular level. “It’s a shift from a clinical to a more biological diagnosis of the disease,” he said.

Addressing genetic function could lead to more effective treatments, Krainc noted. Scientists could someday identify who is more susceptible to a particular neurodegenerative disease and, crucially, how to prevent these people from developing the disease in the first place.

“Genetic testing is important for many reasons. It helps us understand how different patients develop disease. It’s not one size fits all,” Krainc explained. “There are many subtypes of the disease, and genetics helps us find them. This facilitates the development of more targeted therapies customized for such patients.”